The BIG 4: The FOUNDATION of FILM ANALYSIS in THE IB FILM CLASSROOM

There are literally hundreds of ways to analyze a film, but it is often helpful to focus on the BIG 4.

Element #1:

MISE EN SCENE —

Mise en scene literally means “what” is within the frame of the screen.

KEY QUESTIONS —

What is in the frame?

How/Where are characters placed?

How/Where are objects placed?

Why am I seeing this?

EXAMPLE —

Notice the bird motif here. Behind the woman, a small song bird, suggests Marion Crane’s (another bird reference) own frailty and vulnerability. However, notice several larger, more predatory birds behind Norma that suggest he is a predator, ready to attack his unsuspecting prey. In short, the mise-en-scene characterizes her as the prey; him as the predator.

Element #2:

CINEMATOGRAPHY —

Cinematography relates to the involvement of the camera in several ways:

camera angle

camera shot

the distance of the camera from the subject

lighting (or lack thereof)

KEY QUESTIONS —

How is this scene lit?

What position/angle is the camera in the shot?

Does the camera move?

How does the camera move?

What are the characters lit?

What is in focus (out of focus)?

EXAMPLE —

In Nosferatu, notice how the camera is low to make the vampire seem larger than life, and notice how the lighting placement creates the effect that not only does the creature “glide” up the stairs (almost as an apparition), but the darkness is symbolic of his character and intent.

Element #3

EDITING —

Editing concerns itself with how different shots are pieced together in addition to the length of those shots. One may also consider how shots are joined (wipe, dissolve, fade, etc). can be important.

KEY QUESTIONS —

How long is each shot?

How do the edits affect the pacing of the film?

What type of edit is used (dissolve, wipe, cut, etc.) between scenes?

What shot is placed after another shot?

Does one shot interact or create tension with another shot?

EXAMPLE— In Silence of the Lambs, Starling (on the right), a police officer, talks to serial killer Hannibal Lecter (on the left) from a safe distance while the latter sits in his cell. However, the editor skillfully cuts to Lector in increasingly tighter shots to reveal that not only is Starling vulnerable but that their relationship has become emotionally intimate, and she cannot escape his looming presence in her head. In short, Lecter doesn’t just hold the power in the scene, he dominates it.

.

ELEMENT #4

SOUND—

Sound an be natural to the world of the film (diegetic) or separate from the world of the film (non-diegetic), like a song that adds to a mood or feeling.

KEY QUESTIONS —

Is the sound natural to the film?

How does music affect the film?

What sounds are audible in the scene?

Is the sound diegetic (characters on screen can hear it)?

Is the sound non-diegetic (characters on screen can’t hear it)?

What does sound (natural, artificial, diegetic, non-diegetic) do for the scene?

Is the sound is a leitmotif, what does the sound embody?

EXAMPLE — In Apocalypse Now, Coppola juxtaposes the attack of the American helicopters against a hostile Vietnamese village with Wagner’s “Triumph of the Valkyries” to underscore the American’s brash, nearly invulnerable attitude while also elevating the attack to an almost god-like act of power and control.

IMAGES CITED

Coppola, Francis Ford. Apocalypse Now. United Artists, 1979.

Demme, Jonathan. The Silence of the Lambs. Orion Pictures, 1991.

Hitchcock, Alfred. Psycho. Paramount Pictures, 1960.

Jeppsen, Matthew. “The Cinematography of Prisoners,” ProVideo Coalition. 1 January 2015. Web. 24 June 2024.

Kenny, Glen. “‘Making Waves’ Review: How Sound in Cinema Moves Us,” The New York Times. 24 October, 2019. Web. Accessed 24

June 2024.

Murnau, F. W. Nosferatu. Film Arts Guild, 1922.

Singh, Shweta. “Introduction to Mise-en-scene,” Purpose Studios. Web. Accessed 24 June 2024.

Meet the Author, Adam Russell

Adam Russell lives and works in Marietta, Georgia. He is finishing his 22nd year of teaching both film and literature. A 13 year veteran of teaching IB Film, Adam seeks to constantly refine and demystify the art of teaching within the IB framework to help teachers and students find success. In his spare time, he writes feature length scripts and consumes anything and everything that he can get his hands on regarding film: screenplays, films, video essays, books on screenwriting, etc. Comments or questions: write ADAM in the subject line and email streamsemester@gmail.com.

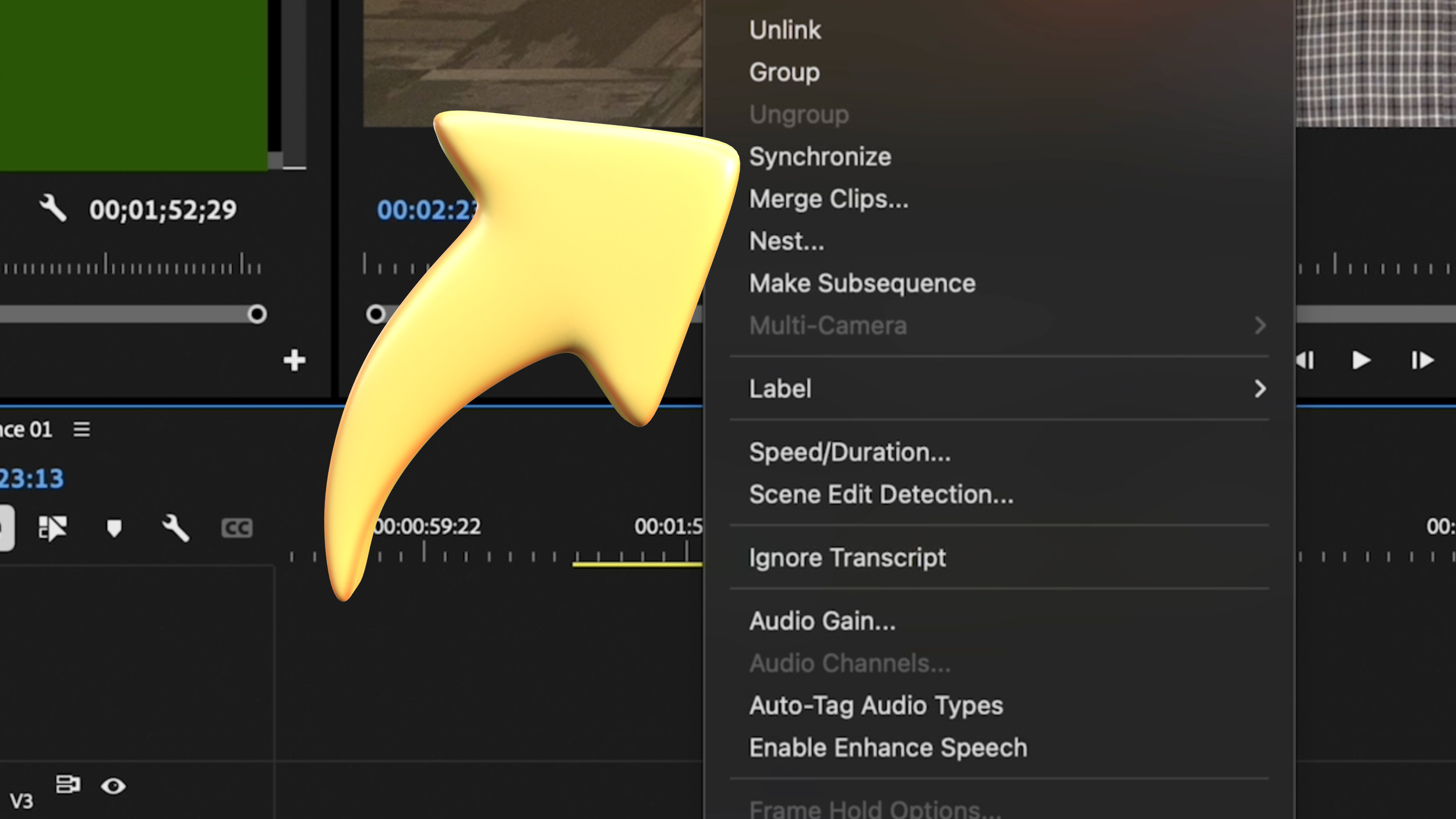

Got shaky footage? No problem! In this quick tutorial, learn how to use Warp Stabilizer in Adobe Premiere Pro to smooth out your shots effortlessly.